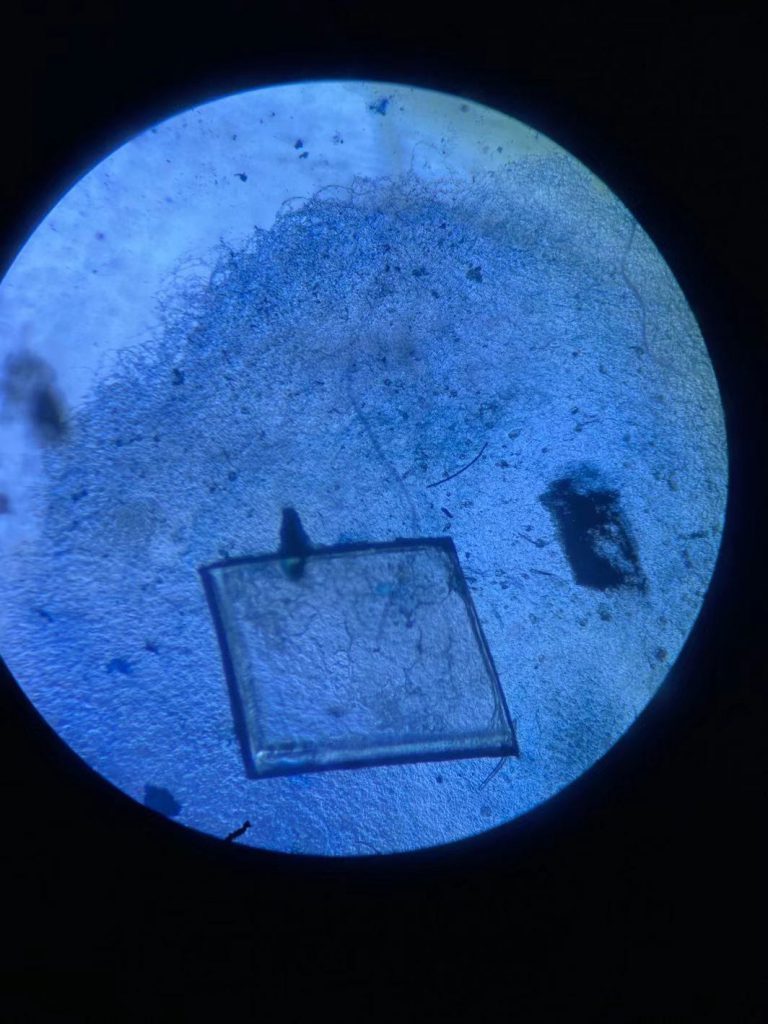

I’m honored to be one of Tumblehome’s newest – and youngest ever – authors, at age 13. It has been such a great experience writing and promoting my book Microplastics & Me, which has been a year-long project, due to be launched on February 1st. The book follows my recent adventures in developing a national award-winning project focused on locating and identifying microplastics as they settle and aggregate along the seafloor.

I’ve now spent several years working on this project and through this time, I’ve begun to realize that the biggest problem in global ocean plastic pollution is not the floating macro and microplastics floating within gyres such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. But, actually, the big problem is the tiny microplastics which gain density and sink to the bottom of the ocean floor, gradually over the course of months, or years, depending on the type of plastic and a whole suite of other factors. As they break down further and further, they gain cumulative surface area and also gain bonding power, as new fresh plastic surfaces are exposed after cracking into smaller pieces, making it easier to bind to other often heavier substances such as heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants, as well as toxic biologicals/organic chemicals. This means that microplastics are far more toxic and far more dangerous to our global ecosystem than larger plastics, and this problem is only getting worse as time goes on.

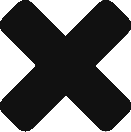

The way to solve this problem is quite complex, and will require a combination of both cleanup efforts, as well as strict and wide-scale prevention measures. However, exactly how this problem should be approached, in terms of priorities, and how to avoid causing other environmental problems during the cleanup process is currently not clearly understood. Given that the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” was not discovered until recent decades, and scientists are only now grasping how to create proper models of plastic flow and accumulation within oceanic currents, there is still much to learn. For one thing, scientists may anecdotally realize that microplastics that are normally buoyant or neutrally buoyant in saltwater are sinking to the bottom of the ocean. This is occurring at a faster and faster rate over time, but yet nobody knows where these “Great Underwater Microplastic Patches”, or GUMP’s as I like to call them, are accumulating. This is the focus of my current research.

Recently, the “Save our Seas 2.0” bill has passed the final committee stage in the Senate at the end of last year, and seems to be regaining some momentum in the media at the beginning of 2020. This bill goes very far in terms of providing continued funding for the NOAA Marine Debris Program. This program helps to “respond to marine debris events”, create new funding and competitions to remove plastic from the ocean, and fund inter-agency collaborations to prevent new plastic waste. What’s great about this bill is that it is not just focused on land-based plastics and

This is certainly not the only government effort to try and curb plastic pollution. A federal-level bill has been proposed to revamp our recycling infrastructure in the US, and to encourage a nationwide plastic recycling deposit program. In NJ and MA, there have also been bills proposed at the state level to prevent the use of plastic bags. In NJ, although the law has recently stalled, there has been some momentum to enact some of the strictest laws in the country regarding plastics. As we have seen in Massachusetts over the past few years, these laws have begun to be adopted on a town by town basis, slowly but surely throughout the Commonwealth. That said, we are now seeing a huge shift back to paper, which has its own environmental concerns as well, but at least it’s relatively biodegradable. And, of course, the biggest city in MA, Boston, has already enacted its city-wide plastic bag ban successfully for well over a year now.

While many of us, focused on marine plastics have been waiting years for some forward-thinking and comprehensive laws to finally be put in place with regard to plastics outside the boundaries of any one nation, these proposed laws do still fall short in many respects.

For one thing, there seems to be a misconception in the starting arguments by some of the bill proposers themselves. Congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici and Congressman Don Young, wrote in their bill summary: “Every minute, the equivalent of a garbage truck full of plastic is dumped into our ocean. According to the United Nations, that’s more than eight million metric tons a year. Plastic bottles, straws, grocery bags, cigarette butts, fishing gear, and abandoned vessels litter the ocean. Currents and winds trap items in debris accumulation zones, also known as garbage patches.” This is all true and is indeed modern science. However, they further state: “We still don’t know how long it takes for plastic to completely biodegrade; estimates range from 450 years to never.” Which, according to a recent Woods Hole conference I just attended a little over a month ago, is not really making the science clear to people. In fact, while the argument is intended to help people understand the gravity of the problem, it is not entirely true. In many cases, most plastics do break down readily within years, due to UV light more so than biodegradation (by a big factor), and the mechanical action of the ocean, in addition to temperature extremes and chemicals. However, the total amount of degradation and how you define “complete” degradation is pretty subjective. At every stage of degradation, plastics pose different problems, and arguably, the more they degrade, the more dangerous they are as they are far more readily absorbed into the global food chain. So, there is still a long way to go as far as public understanding of this issue.

I also strongly believe, as a product of the science fair and other STEM competitions world, that we need to do much more to educate other students my age and younger to ensure that they are aware of this massive problem. This problem is far more likely to cause health effects in our generation, and it is a problem that we will inherit and need to be aware of, whether we like it or not. We will need to be part of solving this problem – and that’s out of necessity, not by choice. So, I think it is critical that we spread knowledge not only about the science behind ocean microplastic pollution, but also to enhance STEM literacy in general. If we are to one day solve problems such as this, or global climate change, or global pandemics, we will surely need to know more than just one or two fields of science. It will take a lot of math, and AI, and engineering, and understanding of chemistry and physics, and other sciences, to tackle issues that are this large in scale – we’re talking three-quarters of the surface of our planet.

In addition, I strongly believe that we need to encourage the general public to take the issue of plastic into their own hands, and provide not only the education, but the resources, to try and come up with smarter solutions to prevention and recycling programs. Rather than continue to fund central recycling programs which always benefit just a handful of companies and organizations, rather than the public at large. The idea of single-stream recycling and curbside recycling, in general, has made it much easier for more people out there to recycle without having to do much sorting. But these programs often generate considerable waste themselves, and ultimately only focus on the most profitable plastics at any given time. Not only that, these recycling programs cost a lot in terms of greenhouse gases, transporting plastics back and forth between retail stores, homes and recycling centers, and back to manufacturers again. I think if more people had access to their own local technology to make it easy to sort and recycle plastics, this would not be an issue. Not only that, we would be more likely to see local communities enabled to create new goods, locally, and thus create new value out of plastic trash.

That is my hope for the world, and maybe this sort of legislation may only be possible when my generation is in charge one day. But for now, I hope that you can all work with me by asking your elected representatives, both in Congress and in the Executive Branch, to continue to support this and other bills that will help rid our oceans of plastic once and for all.

You can find the summary of the bill draft here: https://bonamici.house.gov/sites/bonamici.house.gov/files/documents/190724_Save_Our_Seas_2.0_Summary.pdf

Here is the final bill in whole: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1982/text